Contents:

Awareness and recognition of anxiety disorders in young people have been gradually increasing. A 2020 NHS study found that 1 in 6 children ages 5-16 were identified as having a probable mental disorder. This increases particularly among young women aged 17-22, with 27.2% reported to have a mental disorder. Not all anxiety is clinical, diagnosed or disclosed. Anxiety can be a longer-term condition affecting multiple aspects of a student’s life or acute and focused on particular activities.

Signs a student may be struggling with anxiety

The first sign of anxiety is usually reluctant communication. If, when asked direct questions, a student defers to ‘don’t know’ or says nothing at all a lot of the time, it’s not that they don’t have ideas; it’s a fear of being wrong or expressing themselves incorrectly.

In written tests or assignments, rather than writing something that might be incorrect, there will be gaps and blank answers; failing by default instead of failing because of something they did.

The student may be disproportionately disappointed with anything less than perfect in their work or their answers. Test results could be good but not recognised by the student.

They often anticipate the worst outcomes, fearing that they have got the answer wrong, failed the test, or misunderstood the material. In more severe cases, they will personalise this; watch for students causally calling themselves names, for example, ‘I’m an idiot to have missed this mark’.

Strategies for building confidence

Frameworking

For some students, there is nothing more intimidating than a blank page or empty question line. They’re very concerned with the correct words to use or how to start. For others, they are scared of missing out details, so they will write long, rambling answers that take up too much time.

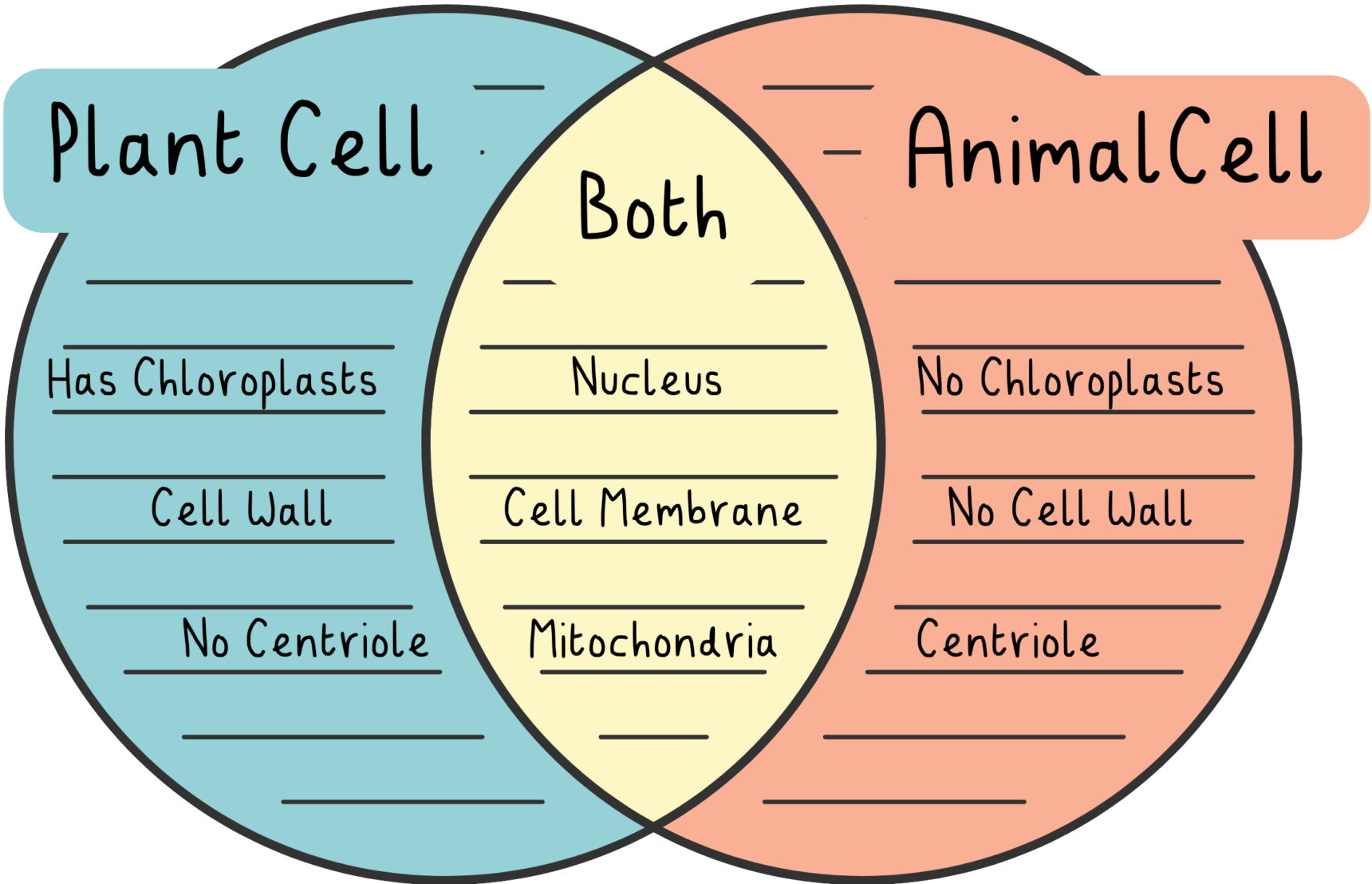

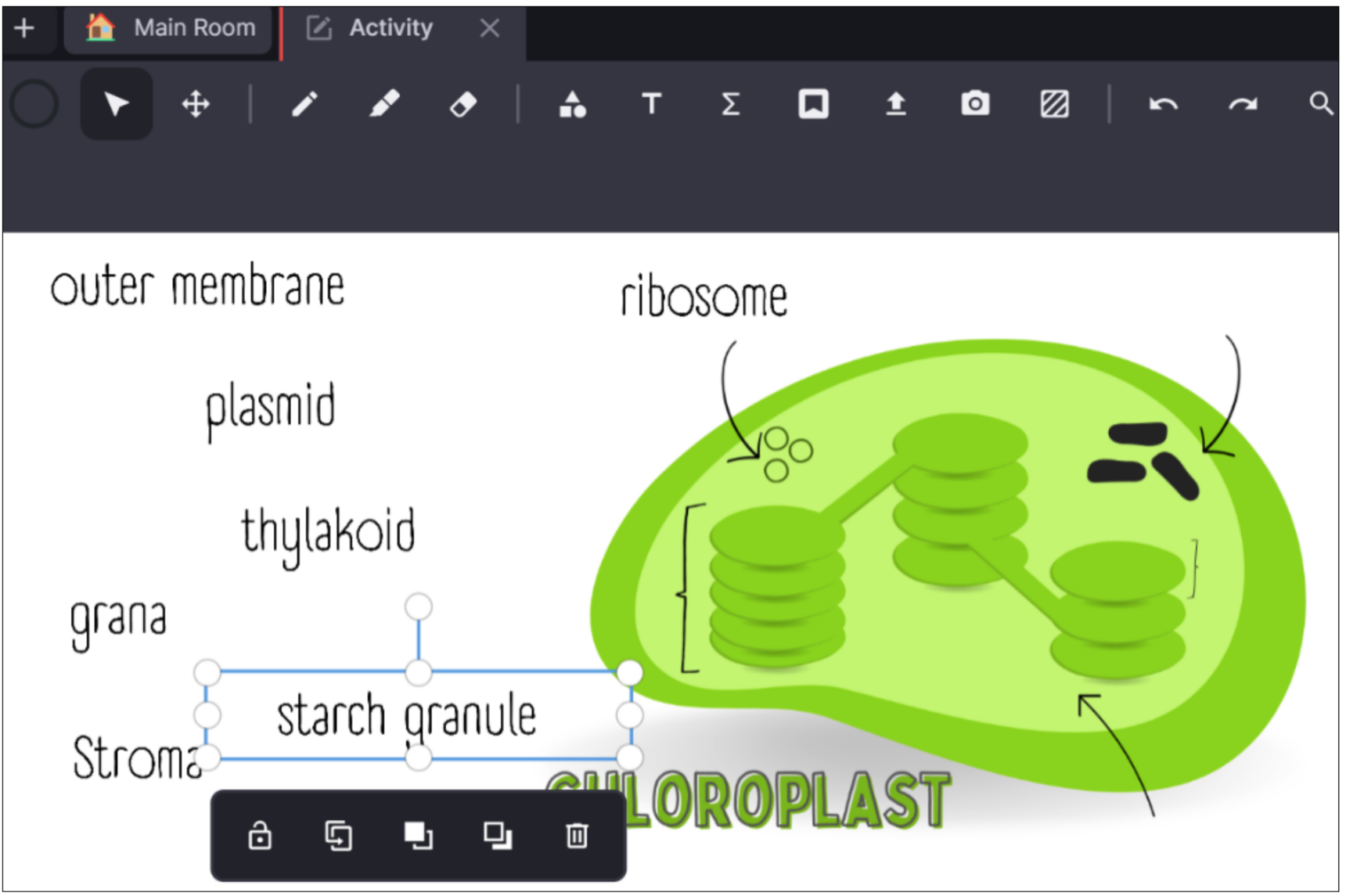

Providing students with a framework for revision and exam questions can help them overcome the barriers of getting started and knowing where to finish. For example, in biology, students are often asked to compare and contrast structures or processes. For revision, a good framework for these questions is to use a Venn diagram, with distinct spatial areas for each feature (the contrast) and an overlap for the things they have in common (the comparison).

As well as being a very clear, visual method of disseminating information, it’s concise. Students with anxiety will either write pages and pages of detailed notes or be too intimidated to write anything at all. The graphic organiser makes it feel manageable.

This can be carried over into answering exam questions. A compare and contrast question can be beautifully answered using a table or graphic organiser. The scaffold for starting is then available to them.

Whatever the question or activity, start by modelling the framework with a full answer. Then, provide the framework for students to complete, and when they seem comfortable, ask them to reconstruct the framework with a new question. The practice should build their confidence enough to try.

Similarly, students can be reluctant to use all the resources available to them, as it can feel like cheating. This is especially true for mark schemes and examiners’ reports. The structure of answers provided in mark schemes can often help provide the framework for student answers. The tips in examiners’ reports can reassure students that they can use a table and won’t be penalised for it.

Constructivist questioning

When asking a question and faced with a very obviously uncomfortable student saying that they don’t know, it can be very tempting to soothe and not push the issue, especially with new students we don’t know very well.

Constructivism is a gentle method to encourage students to develop their answers from ‘I don’t know’ to ‘Maybe it’s…’. The basic principle is that new learning is built on the foundation of existing knowledge. For more modular courses, students may struggle to see how the last module applies to the current one. If we can show them that a principle they know, drawn from either their studies or real life, applies to the subject they’re learning, it can make them feel like they have a more solid start for answering questions.

Another biology example: I could ask a student how the ileum is adapted for its particular function. If they’re not sure, I could compare it to tissues in the lungs where substances are exchanged, and in the second year, I could reinforce this with the cells in the kidney or the structure of the mitochondria. When asked about the condensation reaction, we spend time discussing their real-world experience of what condensation is and how that can help us remember this. We spend time learning common prefixes and suffixes, so when we come across new scientific terms, we can often hazard a guess of the meaning based on prior learning.

Often, students start to recognise their foundations and actively use them for learning.

Non-verbal participation

There’s more than one way to get a student to answer a question than vocalisation or even written answers. If you’re a PMT Education Tutor, the online whiteboard Lessonspace allows you to prepare a number of different interactive activities that feel very low-stakes for students. I’d also encourage you to let them know they can use their notes or textbook to help them with this; it’s all good revision.

Activities that work particularly well include order sorters (dragging and dropping statements into the correct order for a process or event), labelling diagrams with pre-loaded labels, true or false statements that can be sorted into piles, Venn diagrams and keyword matching activities. These short, active techniques really engage students’ brains. They’re able to use their own resources as a safety net, and we can give them feedback and tips as they go.

Safe places to fail

The whiteboard in Lessonspace is and should be a safe place for students to make mistakes without any long-term consequences. In the classroom and for revision, whiteboards and laminates are also useful; they are a place where we can erase mistakes and learn from them. If a student makes an error, let them know that everyone makes mistakes and that it’s an easy one to make. Show them the answer or, even better, support them in getting to it themselves. Then, give them the same question or task again after some time. Chances are they’ll remember and get it right, and hopefully, that’s the thing that will stay with them.

Careful praise

Anxious students, especially those prone to catastrophising or perfectionism, can struggle with direct praise. If you tell them they’re clever or good at this, it’s easy to dismiss these comments as just you being nice because it can’t be about them.

Evidence-based praise that’s depersonalised can be very powerful in confidence building. Instead of ‘You’ve done so well on this question’, tell them that the use of the scientific terms in this answer is excellent, the interpretation of the command words is spot on, and the structure of the answer makes it so easy for the examiner to award marks! It’s much harder to dismiss praise when the evidence for it is there in black and white in front of them.

As an exception to that, sometimes students think they’ve done well in a test because of the tutor or tuition. It never hurts to remind students that they sat that paper, not us. It’s their grade and their hard work that earned them the good grade.

A good number of students who benefit from personal individual tuition will be those who struggle in a group setting due to social phobias or anxiety disorders, especially those students who thrived in lockdown and now struggle in class. Fortunately, the strategies we can use to build the confidence of anxious students have the benefit of being supportive to all students, irrespective of gender, age or diagnosis.

Comments