Contents:

Whether your child has just begun studying GCSE or A Level Physics, is halfway through their course, or is taking exams in 2025, understanding how they can achieve their desired grades will enable you to guide them effectively. In this article, I’ll discuss the process for learning physics, the common barriers to student success, red flags to look out for, the importance of practice, when to get help, and the best help available, including free resources.

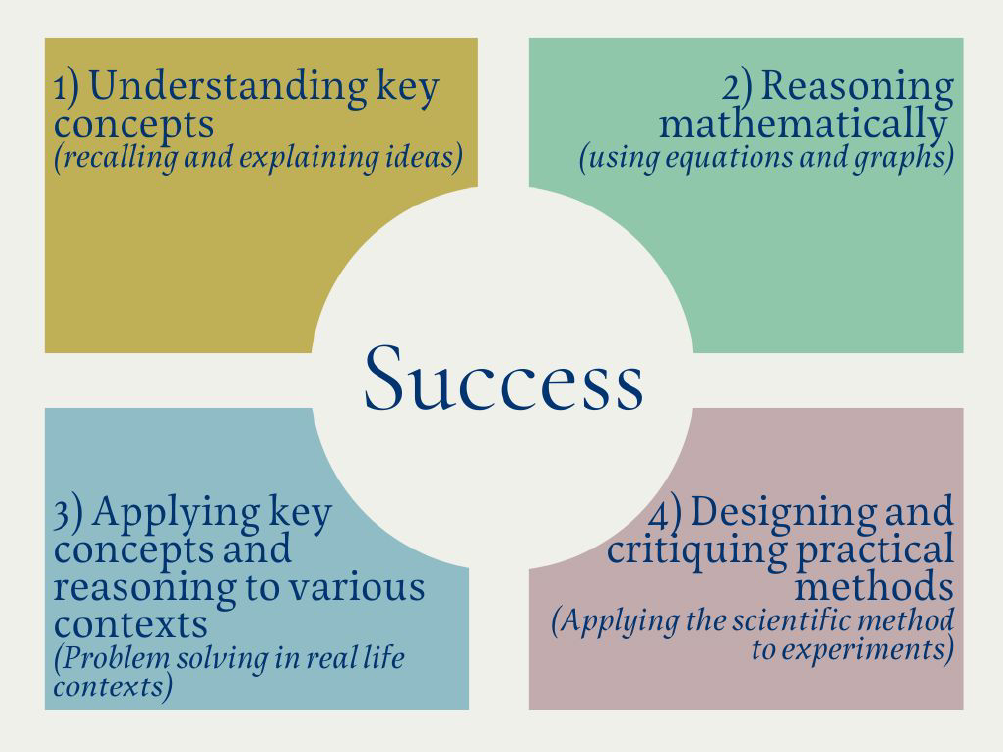

Learning physics: A 4-step process to success

Physics as a subject is rather unique as students must be able to reason logically, conceptually, and mathematically. They must recall key ideas and apply them to real-life situations, as well as use and apply the scientific method in various experimental contexts. The structure of exam questions across different exam boards tends to follow a consistent pattern: recall definitions (~5%); use equations correctly (~30%); offer known explanations (~25%); and apply ideas and equations to unfamiliar situations (~40%).

Thus, the prized skill that leads to high grades is the ability to apply one’s knowledge. Without it, students will be limited to B grades or, at most, a 6 in GCSE and IGCSE. This skill is particularly hard to develop as exam questions often introduce real-life contexts not encountered in the classroom.

For example, when teaching ‘moments of a force’, there are a myriad of real-life scenarios where this physics is seen: the hinges in a door, door handles, wheelbarrows, catapults, joints in the body, bridges, see-saws, and many more. Yet, in the classroom, a student is likely to only experience learning about see-saws and bridges. Teaching every possible context that may appear in exams is simply not possible. So, the emphasis in teaching ought to be on the underlying ideas and skills to help students build the confidence to ‘figure things out’.

The demand on students’ cognitive abilities is thus both varied and high, which is what gives physics its reputation as being a tough subject. While guiding students to success may seem tricky, I’ve identified a clear four-step learning process to success:

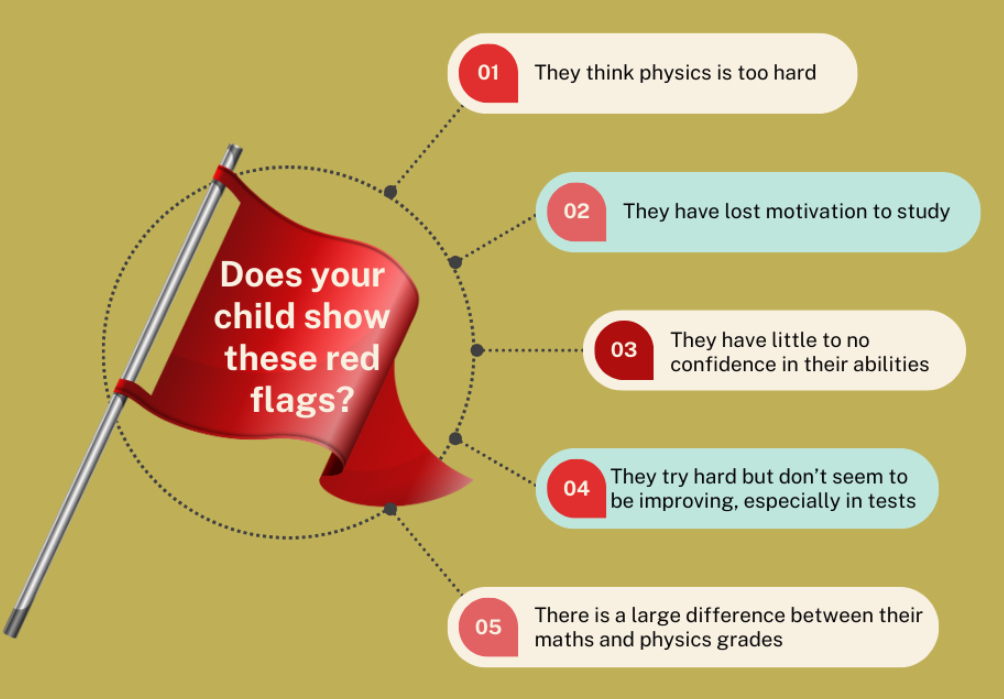

Red flags and barriers to success

In my experience teaching and tutoring physics, I’ve found that students often get caught up in steps 1 and 2. They tend to focus on what they think they need to memorise and may successfully complete straightforward calculations in simpler problems. However, they struggle to progress to applying their ideas. As a result, they remain caught in a cycle of attempting to understand the material and complete homework assignments, before dealing with the next topic at hand.

If your child exhibits some or all of the following red flags, then it is likely they are stuck in this cycle:

There are several reasons why your child may not be progressing in their physics studies. Here are a few common reasons I frequently encounter in my tutoring practice:

- Your child experiences a disconnect between their everyday experience of physics and what is taught in the classroom.

- Your child has a non-specialist physics teacher (this often occurs at GCSE).

- Your child has more than one teacher (this often occurs at A Level). Hence, the linking of ideas between topics does not occur. This negatively affects the development of critical thinking skills, which are essential for problem-solving in real-life contexts.

- The quality of teaching, particularly in explaining concepts, is poor.

- Your child experiences the sense that they’re ‘dumb’ in the classroom due to the arrogance and ego of their peers, or worse, their own teacher. This can cause them to hesitate in asking questions when they don’t understand, which perpetuates the belief that the material is too difficult.

- Your child does not have a SMART goal, and no clear way to measure incremental progress towards that goal.

- Your child has given up because their self-esteem in physics is too low, or they feel it’s too hard as they struggle to understand the concepts.

- Generic teacher feedback, such as ‘work harder’, discourages your child, or test scores are continuously low despite trying.

- Although students may score well on tests, they might find their ability to solve more complex problems inconsistent, which can lower their confidence.

- They believe that physics problems should be difficult, leading to self-doubt even when doing things correctly.

- They focus on comparing their progress to other students’ instead of recognising how they have improved since starting the subject.

- Your child focuses on remembering definitions and explanations, writes summaries, and revises their notes only.

- Your child watches videos to enhance their understanding but does not engage with the material through actions like taking notes or practising questions.

- Your child completes homework problems to a good or even high standard but does not practise past exam questions from their exam board.

- Your child has no exam strategy, e.g. they complete all questions in order rather than optimising their time to gain as many marks as possible.

- Your child may have misconceptions in their understanding that they are unaware of, or that have not been identified for them, which can lead to mistakes. This is commonly observed in students who attempt every question and provide extensive explanations, yet still earn few marks.

- Your child has not been shown how to annotate when problem solving. Drawing labelled diagrams, writing out the information provided in the question, and using clear mathematical processes and notation can prevent students from losing marks due to silly errors.

- Your child is capable of solving maths problems involving algebra and graphs, but struggles to apply the same concepts in physics. This difficulty often arises because, in maths, the variables typically used are limited to ‘x’ and ‘y,’ whereas in physics, we use a broader range of letters from the entire alphabet, including Greek letters. This disconnect frequently needs to be addressed by a teacher.

- Your child might mistakenly believe they should know the answers to physics questions as they read them. Like in mathematics, they need to think critically and puzzle things out. This is especially hidden in explanation questions.

- Your child finds maths more logical and straightforward than physics. In maths, it’s easier to see how exam questions tend to repeat themselves. In contrast, physics presents the same fundamental concepts in new contexts, which makes it harder to identify the underlying ideas. Teachers often do not have the time to go through lots of examples to emphasise that each situation hinges on the same principles.

The value of practice

Physics as a subject has more in common with mathematics than it does with chemistry or biology. To truly improve in physics, the focus must be on practice. In maths, there’s a saying that you stop practising not once you get a question right, but when you no longer get it wrong. Physics is no different. The most effective strategy for your child isn’t watching videos, summarising notes, or rereading them – it’s working through as many past paper questions as possible.

Mark schemes

Having said this, this can be time-consuming and may lack value without proper reflection. A student who practises one hundred questions in succession without checking their work will not do as well as one who checks each answer as they go and takes the time to understand their mistakes. While this may seem obvious, it’s something that many students fail to do. The thought of practising lots of questions can also become overwhelming to students who are struggling to understand key ideas or who are not yet able to take a large task and split it into smaller, more manageable chunks. Consistent practice in short bursts leads to the best results.

Another valuable technique I teach my students, especially when pressed for time, is ‘mark-scheme hunting’. Instead of attempting numerous questions, grab a bunch of past paper questions on a specific topic and read the mark schemes. By collating the mark schemes that share similar elements (e.g. they use the same equations, phrases, or key words), students can compare the way the questions were asked. This is a valuable technique that helps students see past contexts and learn what phrasing in questions provides hints to the ideas being tested.

Formula sheet

Other ways to help your child revise is to take their formula sheet and have them explain what each letter represents, as well as the unit associated with that quantity. This works particularly well for GCSE and IGCSE students who are currently failing or achieving around a grade 4. For A Level students, take this a step further by asking them to sketch the graph of the equation, explaining what the constants are, what the y-intercept may be, and what the gradient represents.

Multiple choice question challenge

In my own tutoring practice, I often help students complete a multiple choice question challenge. Over the course of about three months, students slowly work through 20 papers, each containing 25 multiple choice questions. Each week, they are encouraged to complete up to three papers, mark them, and bring their results to class.

They often start off by scoring around 10 out of 25 and take about 1.5 hours to complete each paper. As we review the questions they struggled with, we highlight and address gaps in their understanding. By the time students get to paper 10, their accuracy has improved to around 18 out of 25, if not higher. Their confidence has soared and they begin to enjoy the problem-solving process. They also start to recognise predictability in the questions, which reduces their completion time to around 40 minutes. The remainder of the practice helps students fine-tune their skills with the goal of consistently scoring more than 20 out of 25 in no more than 35 minutes.

While an increase in 10 marks may seem like a small improvement, for most exam boards, this is equivalent to an increase of more than 10% and can lead to improvements of one to two grade boundaries. In addition, this practice also translates to improvements in their short response questions as they learn to apply fundamental ideas in bite-sized questions, how to annotate and think critically, and how to refine their problem-solving processes to eliminate unnecessary mistakes. These skills cross over to all other types of exam questions, further boosting their overall grades.

Practice is thus invaluable, and how you practise and reflect matters.

Where to get help

As listed in this article, there are many different barriers to success that your child may experience in GCSE or A Level Physics. Luckily, there are many resources available that can help. Since these can be a little difficult to find, I’ve collated a few of them that you can share with your child:

Students should be discouraged from writing their own as this is time-intensive. Instead, encourage them to use those freely available and to annotate them with additional notes.

Rather than simply providing past exam questions, a good book should include practice questions that build up from easy to medium and then to exam-level questions. Crucially, it should provide full solutions. Many physics textbooks fail to provide detailed explanations or only give single number answers to calculations, which does not show the process of how to arrive at the answer. This approach does not support students in their self-discovery or help them improve their problem-solving skills.

Teaching qualifications are especially beneficial for students with learning needs, such as those with English as an additional language (EAL), ADHD, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, or students facing mental health challenges like depression or anxiety. Qualified teachers have studied various techniques to help students from diverse backgrounds succeed.

Examiners and teachers of specifications will often also have had training from that exam board allowing them to impart specific tips and tricks.

My best advice is to try a few tutors in your price range and choose the one your child clicks with best. Look for a tutor who can offer insights into a learning plan that will help your child make progress and succeed.

Alternatively, you can also find full past papers on the site.

For a more refined selection, use a textbook or have a teacher or tutor help you (we tend to have banks of questions or access to exam board specific question banks not available to the public).

Diagrams on Save My Exams are often well drawn and informative.

For pictures, Save My Exams is my go to. However, there’s a limit to how many you can access before you need to sign up. Other materials are also found behind a paywall. Because of these limitations, I often just Google the image rather than visiting the site as the thumbnail images shown can be saved.

When to get help

It’s important to get your child additional help in a timely manner. As soon as they indicate that they are struggling to understand concepts or are unsure about how to tackle questions despite the additional resources listed above, then extra tuition may be required. Many schools offer after school or lunch time sessions at no additional cost, or for a more 1:1 approach, a private tutor may be your best bet.

It’s worth noting that in my own practice, it takes about 12 lessons to help a student improve by a whole grade boundary on topics they’ve already studied. This is, of course, with the proviso that the student applies themselves and completes all the required practice between sessions. For students who have already established that they find it difficult to understand concepts as taught by their current teacher, a tutor can also help with learning topics in advance. This is often more efficient and effective as it allows for the student to understand ideas before they are taught in the classroom. Then when their classroom teacher covers it, the student can engage more and perform better on their homework and school tests, which all build confidence and lead to improved final grades.

Comments